Springbank Park is a 300 acre parkland situated in the middle of the city of London, Ontario. Home to around 30 kilometres of walking trails, a massive playground, a children’s amusement park, a carousel, and more geese than you can shake a stick at, it is a park that is used constantly and continuously by both denizens of the city and outside visitors. Chances are, if you ask a Londoner “Hey, are there any good parks around here?” they will tell you “Springbank” even if they live on the edge of one of London’s numerous other parks. Contrarians might tell you “Gibbons Park” and that is a good one, but Springbank has everything you could ever want in a park.

Early History

The area that is now Springbank Park lies along the Thames River. It’s an area that has been continuously occupied by humans for an extremely long time. Evidence of human occupation has been found as early as the Middle Archaic Period (3050-2550 B.C.). For reference, this is around the same time that the Greek Bronze Age began, when Stonehenge began to be erected, and around the time Egypt was on its third ruler of the First Dynasty. From then until the European settlement of southwestern Ontario there is evidence that the area of Springbank Park has hosted human communities. The Museum of Ontario Archaeology has catalogued over 6000 separate pieces of evidence to this end, including human artifacts, animal bones, and scraps of plant remains.

After the arrival of Europeans, of course, the situation didn’t change much. There are artifacts from European settlers that have been found in the Springbank Park area that match up with patterns of early settlers: nails, glass, ceramic pottery, kitchen utensils, and other items of domesticity. While no permanent settlements ever appeared in the Springbank Park area, it has always been a favourite place for human beings to rest, or play.

Early Modern History

The real origins of Springbank Park as we know it today date back to 1877. At that time, the City of London was a growing concern, filled with breweries, newspapers, banks, mills, and churches. Two years earlier, the Blackfriars Street Bridge had been constructed across the Thames on the north end of the community, to connect the suburbs of Petersville and Kensington to the City of London proper. A city growing as prosperous as London needed a continual amount of new infrastructure, and the origins of Springbank Park are actually based around this need. As the Victorian era of the Canadian colony wound on, urban citizens clamoured for the sorts of amenities they had in the cosmopolitan cities of the world; in this case, the people of London wanted running water. To this end, $400,000 (nearly $8.7 million in modern Canadian currency) was promised by the city to fund the construction of a waterworks that would be the central mechanical feature of this new system of running water.

The city cast about to find a site for this new water plant and eventually settled on a place that Londoners today typically know as “Reservoir Hill”. At the time, it was called Hungerford Hill, and it was most famous as the site of a couple of small battles during the War of 1812, including a raid by the Middlesex Militia on American troops who were on a raiding mission in the closing days of the war in 1814. The hill was chosen primarily because it was already known as a good site to draw power from the river. The hill sat next to what was then Coombe’s mill, a large flour mill on the western bank of The Thames River near the village of Byron, Ontario. In addition to the water pumping station, the City also commissioned the construction of the Springbank Dam, a structure that, after a number of rehabilitations and long-running municipal arguments, remains in the river today. There were several local springs in the area, and these were engineered to run into collecting ponds that then filled a reservoir on Hungerford Hill. The pumping station was designed to take that collected reservoir water and use gravity pumps to push water through the pipes to the connected homes and businesses of London.

You can still see the original pump house today, in Springbank Park or if you look quickly as you’re driving along Wonderland Road. One of the original holding ponds is also still in existence, near Storybook Gardens. A steam plant was added for additional power generation in 1881, but it no longer remains. The area around the waterworks became a popular spot for Londoners to spend an afternoon picnicking, and the area at first gained the name “Chestnut Park”.

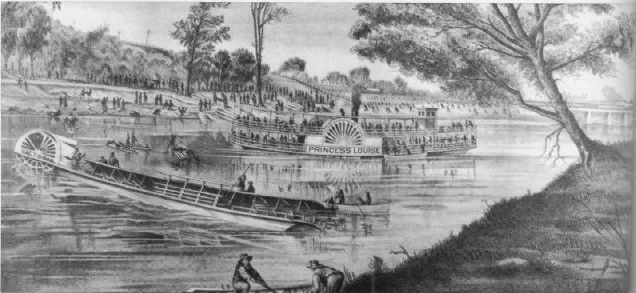

Rolling On The River, or, The Wreck Of The Victoria

The gathering of well-heeled Londoners at Chestnut Park on the banks of the Thames led, predictably, to a growth in businesses looking to cater to these people. The most lucrative of the bunch were the river transport entrepreneurs, who realized that the Thames made a perfect highway to shuttle picnickers to and from the park. The first of these was The Thames Navigation Company, founded in 1878 to provide ferrying services for those looking to frolic in the pastoral setting. By 1879 the park was so popular that a refreshment stand opened up next to the pumphouse. In that same year, the Thames Navigation Company got some competition, in the form of a company called the London And Waterworks Line. The competition between them was fierce. The Thames Navigation Company put a second ferry on the river, put a live band on the original ferry, and instituted “moonlight cruises” at a premium, for the romantics of London. The two companies did a brisk trade and eventually the refreshment stand was expanded into a hotel and Chestnut Park became something of a destination spot of holidays and families.

Unfortunately, economic competition also led to a certain recklessness. In May of 1880, the London And Waterworks Forest City and the Thames Navigation Company Victoria collided on the water, after a series of mishaps that started when the passengers on both ships reached out to try to grab each other’s hands. The ships had come close to each other before but this was the first time that they had actually run into each other. Luckily there were no injuries from the incident; the next accident would be much more grim.

A year later to the day – May 24th, 1881 – the Victoria Day celebrations were in full swing at Chestnut Park. A large crowd had gathered at the docks to take the ferry home; when the TNC Victoria arrived at the docks a group in excess of 600 people clamoured aboard to be taken away. This was more than the Victoria could safely carry, which is kind of like saying that piling 50 people into an elevator exceeds the operating capacity. That is to say, it was obviously too many, and the man in charge knew it. Despite this, the Victoria set sail back to the city in the early evening.

The problem with putting too much weight onto a ship is that is runs quite a bit lower in the water than it normally does. Because of this, the ship ran into an object it would normally have passed right over. The hull was breached, Victoria took on water, and the panic of the mass of passengers caused the ship to tilt. As it tilted, the boiler came loose and crashed through the ferry’s upper deck, which subsequently collapsed. Between those who drowned, those who were crushed by the upper deck’s collapse, and those who were scalded to death by the boiler, 182 people lost their lives.

The problem with putting too much weight onto a ship is that is runs quite a bit lower in the water than it normally does. Because of this, the ship ran into an object it would normally have passed right over. The hull was breached, Victoria took on water, and the panic of the mass of passengers caused the ship to tilt. As it tilted, the boiler came loose and crashed through the ferry’s upper deck, which subsequently collapsed. Between those who drowned, those who were crushed by the upper deck’s collapse, and those who were scalded to death by the boiler, 182 people lost their lives.

The wreck of the Victoria largely put an end to the ferry business on the Thames. A series of deadly floods in 1883 did the industry no favours, but the advent of trains and automobiles as easy transport solutions for Londoners finished it off. 1898 would be it’s final year; after that, full time ferry service as a private industry would be no more.

A Wonderland of Amusements

One of the things that really killed off ferry service to the area was the growth of the streetcars, and London Street Railway. The city of London had taken charge of Chestnut Park after the wreck of the Victoria and had added new features to the park, including paths, benches, and swings for children. Officially renamed Springbank Park in 1894, the area’s popularity in the final years of the 19th Century convinced the London Street Railway company to extend streetcar lines to the park. With the streetcar lines came electricity, and night-time lighting became one of Springbank’s biggest attractions, at a time when electric lighting was still the exception rather than the rule.

With increased popularity, paths became roads, and tennis courts and lawnbowling areas were installed. By 1914 the next stage in Springbank’s development came, in the form of an amusement park run by the Victor Amusement Company. Included in this amusement park were a campground and a zoo. By 1920 this expanded to include a Ferris wheel, bumper cars, a funhouse, a penny arcade, and a bowling alley. A rollercoaster called the “Cannon-Ball” was built at the south end of the park, and a carousel was added. In 1923 a miniature steam train was added; this is the Springbank Flyer, which was converted to run on diesel fuel in 1965 and was transferred to its current location outside Storybook Gardens in 1998. An aerial swing was also added in 1927. In 1935, the Wonderland Gardens concert hall opened up and became quite popular as a place to see the hottest big bands of the day. Although there is no actual proof, the legend is that Guy Lombardo, a bandleader who eventually gained fame as the premier New Years Eve entertainment man, played the first show at Wonderland Gardens.

Victor Amusements did a brisk business until the outbreak of the Second World War, when the crowds stopped coming in large numbers. In 1942 the park went up for sale; a few of the features, notably the train and the carousel, remained open as they were run independently and were still profitable. Fortunes changed again in 1958 when Storybook Gardens opened. Storybook Gardens, still the main tourist draw of Springbank Park to this day, grew out of the purchase of the old zoo that Victor Amusements had begun with in 1914. The zoo was expanded and rebranded with the theme of Mother Goose’s nursery rhymes.

One of the things that really killed off ferry service to the area was the growth of the streetcars, and London Street Railway. The city of London had taken charge of Chestnut Park after the wreck of the Victoria and had added new features to the park, including paths, benches, and swings for children. Officially renamed Springbank Park in 1894, the area’s popularity in the final years of the 19th Century convinced the London Street Railway company to extend streetcar lines to the park. With the streetcar lines came electricity, and night-time lighting became one of Springbank’s biggest attractions, at a time when electric lighting was still the exception rather than the rule.

With increased popularity, paths became roads, and tennis courts and lawnbowling areas were installed. By 1914 the next stage in Springbank’s development came, in the form of an amusement park run by the Victor Amusement Company. Included in this amusement park were a campground and a zoo. By 1920 this expanded to include a Ferris wheel, bumper cars, a funhouse, a penny arcade, and a bowling alley. A rollercoaster called the “Cannon-Ball” was built at the south end of the park, and a carousel was added. In 1923 a miniature steam train was added; this is the Springbank Flyer, which was converted to run on diesel fuel in 1965 and was transferred to its current location outside Storybook Gardens in 1998. An aerial swing was also added in 1927. In 1935, the Wonderland Gardens concert hall opened up and became quite popular as a place to see the hottest big bands of the day. Although there is no actual proof, the legend is that Guy Lombardo, a bandleader who eventually gained fame as the premier New Years Eve entertainment man, played the first show at Wonderland Gardens.

Victor Amusements did a brisk business until the outbreak of the Second World War, when the crowds stopped coming in large numbers. In 1942 the park went up for sale; a few of the features, notably the train and the carousel, remained open as they were run independently and were still profitable. Fortunes changed again in 1958 when Storybook Gardens opened. Storybook Gardens, still the main tourist draw of Springbank Park to this day, grew out of the purchase of the old zoo that Victor Amusements had begun with in 1914. The zoo was expanded and rebranded with the theme of Mother Goose’s nursery rhymes.

Slippery The Sea Lion

As part of its attempt to draw tourist crowds for the grand opening, Storybook Gardens bought two seals from California. One of these seals, however, gave Storybook’s owners a fair bit of trouble. This seal, who afterwards gained the nickname of Slippery The Sea Lion, somehow managed to escape his pool and found his way into the Thames River. Despite the efforts of Storybook staff to recover him, he followed the river all the way down into Lake Erie. It wasn’t until Slippery reached the American side of the lake that he was recaptured, near another amusement park (Cedar Point) close to Sandusky, Ohio. Still trying to promote their business to the full extent possible, Storybook Gardens and the Toledo Zoo cooked up an international incident.

As part of its attempt to draw tourist crowds for the grand opening, Storybook Gardens bought two seals from California. One of these seals, however, gave Storybook’s owners a fair bit of trouble. This seal, who afterwards gained the nickname of Slippery The Sea Lion, somehow managed to escape his pool and found his way into the Thames River. Despite the efforts of Storybook staff to recover him, he followed the river all the way down into Lake Erie. It wasn’t until Slippery reached the American side of the lake that he was recaptured, near another amusement park (Cedar Point) close to Sandusky, Ohio. Still trying to promote their business to the full extent possible, Storybook Gardens and the Toledo Zoo cooked up an international incident.

The Toledo Zoo made a claim that, because Slippery was found in American waters, they were going to keep him instead of returning him to Storybook Gardens. When this decision was reported in London the London citizenry flew into an outrage, demanding that Slippery be returned to his Canadian home. Officials from both zoos met in Toledo and negotiated the return of Slippery to London, along with Lucky, a baby puma that the Toledo Zoo gave Storybook Gardens as a gift. The city threw Slippery a parade upon his return that 50,000 attended (at the time, half the city of London’s population) and Storybook Gardens drew a massive crowd when he was placed back into his home pool.

Springbank Today

In 1961 the village of Byron was formally annexed into the City of London and the city took over the operation of Springbank Park (except for Storybook Gardens, which continues to operate privately). The park today features wide open spaces, shady trees, and enough barbecue spaces to accommodate an entire city’s worth of holiday-celebrating families. Also featured are a large children’s playground with state-of-the-art equipment and a full size wading pool. Walking trails criss-cross the park and also connect Springbank Park to a number of other parks and nature areas in the surrounding parts of the city. While I’ve never tested this, it’s said that you can make the 10 kilometre journey from Byron to Downtown London without needing to drive on regular city roads; just walk through the interconnected parks and you’ll end up in the heart of the city.

In 1961 the village of Byron was formally annexed into the City of London and the city took over the operation of Springbank Park (except for Storybook Gardens, which continues to operate privately). The park today features wide open spaces, shady trees, and enough barbecue spaces to accommodate an entire city’s worth of holiday-celebrating families. Also featured are a large children’s playground with state-of-the-art equipment and a full size wading pool. Walking trails criss-cross the park and also connect Springbank Park to a number of other parks and nature areas in the surrounding parts of the city. While I’ve never tested this, it’s said that you can make the 10 kilometre journey from Byron to Downtown London without needing to drive on regular city roads; just walk through the interconnected parks and you’ll end up in the heart of the city.

The historical parts of the Park are still on display if you know where to look. The remains of the old waterworks are still there, as is the Springbank Dam, which is easy to get to: a wooden stairway exists right behind the playground that takes you right down to the dam site. When the water level on the Thames River is low, you can also sometimes see the remains of the metal part of the hull of the Victoria, still resting on the bottom of the river well over a century later.

Whether you want to hike, jog, play, cook, celebrate, avoid the roads, or find that elusive moment of zen, Springbank Park is London’s premier destination.